(Townsend, 1993) Defines

poverty as being unable to partake in society because of a lack of resources

available to you. Meaning participation or consumption are dependent on

financial resources and affordability of them. However, it is still possible to

be in poverty with financial support.

A lack of participation in decision

making or a violation of human dignity are just examples of non-material

aspects of poverty of which make you powerless. (UKCAP, 1997) argues that

choices available to you and opportunities defines poverty more than your

income. Because you can have large amounts of income, but a denial of rights and

equality can differentiate you between poverty and non-poverty.

This essay will discuss how

policy makers addressed poverty issues within the education system during the

1870 Fosters education act, The 1867 2nd Reform act and the 1902 Balfour

education act.

It will use theories from Karl

Marx, Emile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu to look at these policies from various

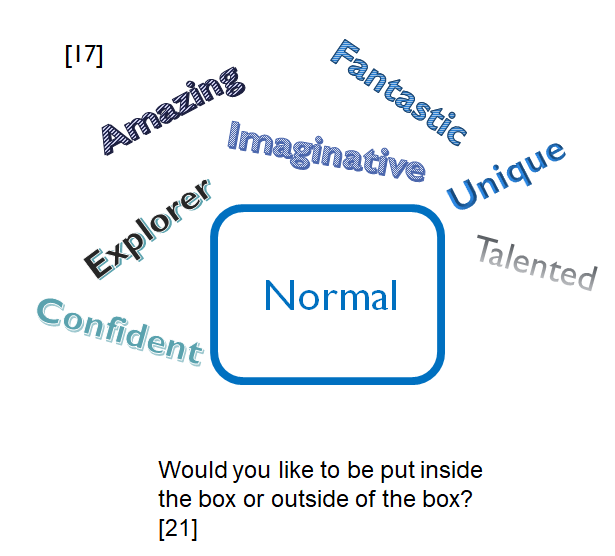

angles. And compare these policies to today’s contemporary ideas of which are

currently being implemented into the education system to address or further

widen the gap between poverty and the different classes.

The 1870 education act was a

policy implemented by the government to assure all children received at least

five years of compulsory education. The reason for doing this was due to

industrial development such as factories needing workers who had adequate

literacy and mathematical skills and an increase in the urban population in

Britain (Bartlett and Burton, 2016).

However, the working class

opposed to the government’s policy on compulsory education. If their children

had to attend school then the parents could no longer benefit from their

child’s services in the home and their contributions to the family budget, such

as house or farm work consequently reducing their income (Hurt, 1979). This

then ultimately widened the gap further by ‘making the poor poorer’.

It was not just the working

class who had discrepancies with this policy. The concerns amid the middle and

upper classes where that an educated working class will no longer obey their

superiors and be unsatisfied with their menial jobs (Bartlett and Burton, 2016)

causing a scare amongst the upper classes of a loss of dominance over the

working class and a fear of them becoming equals.

Marx argued that by the

government taking over the education board to fund free compulsory education,

the upper class would inevitably be reproducing their own structural

inequalities, such as the poverty gap, plutocracy and totalitarian. He believed

that state run schools would be used as superstructures to oppress the working

class by only teaching them menial skills and attributes such as labouring and

working ‘for’ the dominant class (Bailey, 2010). While the upper classes would

be taught how to manage and run the businesses.

Nevertheless, policy makers

continue to broaden the social class divide and increase poverty in education.

(Grammatical error; Schools, 2016) reports that the modern-day government are

supporting new grammar schools to be built within Britain.

This pushes out a meritocratic

apparition of social mobility. (Gorard & Nadia Siddiqui, 2018) cite that by

clustering the advantages of the upper class into grammar schools has a

probable dangerous effect on society, such as affecting children’s social

skills, attitudes and developing a lack of democracy in generations to come. As

well as the problems discussed in Marx’s theory.

(Tawney, 1931) argues that the

social class issue can be found throughout the education system, yet it is

denied and not ever conversed. Pupils achieve better grades in grammar schools

than in comprehensive schools, and students who do not attend grammar school

achieve worse than they would if grammar schools did not exist (Orford, 2018). Reasons

being, that these schools attract the more qualified and experienced teachers

and educators, fixing failure into the working class by putting them into

devalued educational spaces away from the upper class, to allow them to

monopolise mobility (Raey, 2006) and leave the working class behind.

Reintroducing selection into

education would do little to improve the diversity of the future. However,

although both policies argue to be meritocratic in some form or another, it is

evident that Marx’s view of social reproduction and control of the means of

production by the elite does not efficiently address the impact of poverty on

education.

Significant political changes

had happened in Britain during 1867 and the working-class men were now given

the right to vote (Bartlett and Burton, 2016) so it was imperative to ensure

that they were educated enough to understand what they were voting for.

However, this policy was a way

of reproducing inequality. (Hurt, 1979) cites that what seemed to be a

democratic nature by the school boards, the genesis aroused to find that this

was a way of influencing the working-class vote, by educating them only on how

to vote for the conservatives and educating them only what they wanted them to understand

and vote for (Bartlett and Burton, 2016). Therefore, grooming them for their

own gains and using a policy of democratic falsehood to disguise it.

Both Durkheim and Weber’s

theories are similar to liberal principles and the apprehension and belief in

individuals actively participating in social life. They both believe that

democracy is the best way to promote individual freedom (Prager, 1981).

(Giddens, 1972) refers to

Durkheim’s views that society can only survive if there is homogeneity between

everyone. Education plays a key role in enforcing this by fixing it into a

child’s mind from the early life. Such as, influencing them on who they should

vote for.

It does this by implementing

essential similarities from social life demands into school life. For example,

teaching specific skills like rule following, self-control and boundaries.

(Durkheim, 2012) believed that by being in a school environment, children will

learn more widespread knowledge than they would in a family environment.

Meaning that by putting the

working class into compulsory education from an early age, they would have more

power over them and be able to guide and influence them to some degree. And

Weber’s theories had more of a concern over formal structures of rule and power

which resembled this democratic uncertainty (Thomas, 1984).

In 2011 a policy was put into

place by the local authority called ‘pupil premium’ This was a modern-day

attempt at abolishing this power and gaining more equality within the education

system by giving the ‘poorer’ pupils funding so that they gain an equal

schooling experience to the middle and upper-class pupils.

The money is to be spent by

the school to improve the attainment of the eligible child (Tickle, 2016) and

close the gap made by poverty.

Yet, pupils eligible for pupil

premium are not on the lowest household income in the schools and are not the

most educationally disadvantaged. There are lots of children living on the

poverty line who are not eligible for pupil premium because they do not qualify

for free school meals. Because, it is attached to benefits and does not

consider income (Allen, 2018), whereas if a family is ‘working poor’ they are

not eligible for either the free school meals nor the pupil premium. So, the

‘poorest’ pupils still suffer the most.

The 1902 education act

established secondary and grammar schools. It also developed a system for free

places and funded scholarships for a select few ‘poor’ children to attend

grammar school (Simon, 1965).

This new policy abolished the

school boards and brought in ‘local education authorities’ (LEA’s) which gave

the government complete authority over education through local councils and

created a unified national system of education. Prior to this, school boards

where elected democratically by local people.

Although the working class now

had access to secondary schools and funded scholarships at grammar schools,

this did not mean that they would always ‘fit in’ and be accepted equally by

the dominant class. A majority of the time they would feel, as (Reay, Crozier

and Clayton, 2009) cites “like a fish out of water” within the upper-class

institutions.

This argument is similar to

Bourdieu’s ‘Habitus’ theory that the way that we perceive the social world of

which we are in are shared by people with the same background. For example, we

are fixed on how to act according to our world around us, but if we are not

from that background on the social structure. The way to act, speak and dress

for instance, is not already set on our minds and we must then change to fit

in.

(Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977)

suggested that education reproduces society by passing on cultural values,

Bourdieu’s economic capital meant that the working-class pupils need the

material goods such as uniforms, internet access and technology that the

dominant classes acquire, in order to compete for their educational success.

Without these necessities’

pupils can struggle to achieve. In contemporary Britain, a majority of

student’s homework requires internet access whether it be to research or to use

the school’s website and apps to complete it online (Branam, 2017). This is

otherwise known as ‘the digital divide’.

Another example of ‘the

digital divide’ is Schools using text messages as a means of contacting and

informing parents, this is on the assumption that all parents have a mobile

phone. And if this is the case, then that child can be left out of learning activities

and educational events because the parent was un aware from not being able to

receive the text message.

(Bourdieu, 1990) sees

meritocracy as an allegory and pupils are directed to trust that failure and

success is based on quality and excellence, nevertheless, it appears to be our

class background which governs what we achieve and how well we do in education.

Meaning that our motivation, intelligence and ideas have less of an effect on

our grades and life success than our class background does.

Successive governments and educationalists through history have attempted to put policies into place to address the impacts of poverty and provide an equal education for all, but as we can see, with the middle and upper classes still at an advantage despite various attempts through history and the present day, it seems incomprehensible to close the gap on such a deep routed issue.

References

Allen,

B. (2018). The pupil premium is not working: Do not measure attainment gaps.

[Blog] Musings on education policy. Available at: https://rebeccaallen.co.uk/2018/09/10/the-pupil-premium-is-not-working/

[Accessed 21 Mar. 2019].

Bailey, R. (2010). The

Philosophy of education. London: Continuum, p.111.

Bartlett, S. and Burton, D.

(2016). Introduction to Education Studies. 4th ed. SAGE, p.76.

Bartlett, S. and Burton, D.

(2016). Introduction to Education Studies. 4th ed. SAGE, p.71.

Bartlett, S. and Burton, D.

(2016). Introduction to Education Studies. 4th ed. SAGE, p.78.

Bartlett, S. and Burton, D.

(2016). Introduction to Education Studies. 4th ed. SAGE, p. 162

Bourdieu, p. (1990).

Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. 4th ed. Sage Publications (CA).

Bourdieu, P. and Passeron, J.

(1977). Reproduction in education, society and culture. London: SAGE.

Branam, J. (2017). Online

homework is a problem for 5 million families without internet at home. Covering

Innovation & Inequality in Education.

Durkheim, E. (2012). Moral

Education. New York: Dover Publications, pp.17-33

Emile Durkheim, Selected

Writings, ed. And trans. (Anthony Giddens, Cambridge, England: Cambridge

university press, 1972)

Grammatical error; Schools.

(2016). The Economist, 8, p.40.

Hurt, J. (1979). Elementary

schooling and the working classes 1860-1918. Toronto: Routledge, p.3.

Hurt, J. (1979). Elementary

schooling and the working classes 1860-1918. Toronto: Routledge, p.81.

Orford, S. (2018). The

capitalisation of school choice into property prices: A case study of grammar

and all ability state schools in Buckinghamshire, UK. Geoforum, 97, pp.231-241.

Prager, J. (1981). Moral Integration

and Political Inclusion: A Comparison of Durkheim’s and Weber’s Theories of

Democracy. Social forces, 59(4), pp.918-950.

Raey, D. (2006). The Zombie

stalking English schools: Social class and educational inequality. British

journal of educational studies, 54(3), pp.288-307.

Reay, D., Crozier, G. and

Clayton, J. (2009). ‘Fitting in’ or ‘standing out’: working-class students in

UK higher education. British Educational Research Journal, pp.1-18.

Simon, B. (1965). Education

&the Labour movement 1870-1920. London: Lawrence & Wishart, pp.165-175.

Stephen Gorard & Nadia

Siddiqui (2018) Grammar schools in England: a new analysis of social

segregation and academic outcomes, British Journal of Sociology of Education,

39:7, 909-92

Tawney, R. (1931) Equality

(London, Allen and Unwin).

Thomas, J. (1984). Weber and

Direct Democracy. The British Journal of Sociology, 35(2), pp.216-240.

Tickle, L. (2016). How should

schools spend pupil premium funding?. The Guardian. [online] Available at:

https://www.theguardian.com/teacher-network/2016/oct/18/how-should-schools-spend-pupil-premium-funding

[Accessed 17 Mar. 2019].

Townsend, P. (1993). The

International Analysis of Poverty. Harvester Wheatsheaf.

UKCAP (1997). Poverty and

participation. London: UK Coalition against poverty